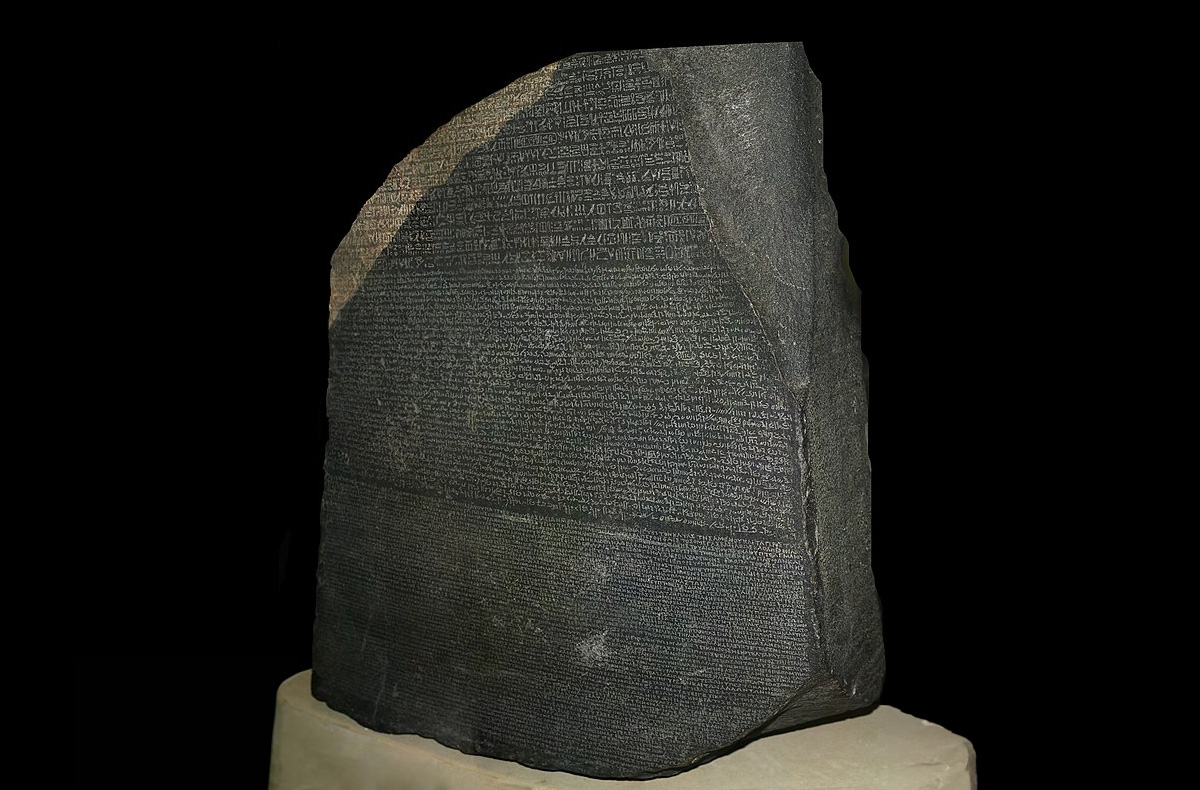

The Rosetta Stone, now valued as one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of all time, was once valued for something else entirely – its sturdiness as an actual stone. Centuries ago, Egyptian builders found this large slab of black basalt, ignored its now-invaluable engravings, and used it to fortify an ancient wall near the Egyptian town of Rashid (Rosetta). There it sat for centuries, dutifully carrying out its task of being a wall.

The Discovery of the Rosetta Stone

It was not until Napoleon’s occupation of Egypt during the late 1700s that the stone, its engravings still intact, was discovered. While renovating Fort Julien, French soldiers unearthed the massive slab, and though its true worth was not immediately understood, its extensive engravings drew attention from command, and the stone was ultimately sent back to Europe for further study.

The Stone’s Engravings

The stone, measuring approximately 4’x2’x1’, bore a text that was written in triplicate but in different scripts, meaning it had the same message written in Greek, hieroglyphics and demotic, the latter two of which had become incomprehensible to scholars over the passage of time.

Lost Knowledge – Hieroglyphics and Demotic

Hieroglyphics were one of civilization’s very first forms of writing, having been developed over 5,000 years ago (3200 BCE). The information written in demotic script was not as old, but much more plentiful, and was believed to document major historical events in Egypt and the surrounding region.

For centuries, scholars could do little more than look at the pictures in the hieroglyphics and the intricate swirls of the cursive demotic and guess as to their meanings. For centuries, researchers and academics the world over tried, and failed, to decipher them.

The Key to Deciphering the Lost Knowledge

The key was that third language, Greek, which was of course still well understood when the stone was discovered. So with the Rosetta Stone in hand, it was theorized that the Greek portion could be used to crack the writing systems of the other two sections. If successful, this would give scholars the ability to read countless other tablets, papyrus scrolls, and other engravings whose meanings had been lost to the ages.

Historians read the Greek portion, and quickly determined that the actual message on the Rosetta Stone was largely insignificant. It was a standard religious decree from King Ptolemy’s council (and was largely the King talking about how wonderful he was). What was significant, however, was that scholars were now well on their way to using the Greek section to try to “decode” the other two forms of writing and unlock tomes of previously unreadable text and artifacts.

The Race to Decode Hieroglyphics and Demotic

Researchers and academics now had clues, but it was not as though they had been handed a trilingual dictionary and grammar guide. Seeing how the Greek translated to demotic and hieroglyphics was a painstaking puzzle, and teams of scholars struggled for years.

A race to decode the stone began in Europe, and the two leading researchers were Thomas Young, a British physicist, and Jean-François Champollion, a French scholar. The situation was not unlike Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla’s “War of the Currents” to see who would discover the first great leap forward.

As was often the case, there was a bit of nationalism at play as the two sides rushed to unlock the stone’s secrets. Both Young and Champollion made major achievements in decoding hieroglyphics and demotic, but in the end, it was the French Champollion who made the major breakthroughs. As the story goes, Champollion finally cracked the code, screamed out “I’ve got it,” then passed out and remained unconscious for several days.

With the new knowledge of how hieroglyphics and demotic were read and written, archaeologists and researchers around the world could now dive into the previously untapped messages from early civilization. Once lost documents and treasures had regained their meaning.

Possession of the Stone

Though the French had discovered the Rosetta Stone, it was relinquished to the British crown following Napoleon’s defeat in Egypt. Its transfer was an official term in the Treaty of Alexandria, and the stone came to symbolize victory during that era of colonial conquests, in regard to both military might and cultural advancement.

The Stone Today

The Rosetta Stone remains in England to this day, and is housed in the British Museum in London. A 3D model can be viewed here. Egypt has made efforts to have the stone returned to its birthplace in Egypt, but as a vestige of the colonial era’s perspectives and beliefs, those requests have fallen on deaf ears.