Forensic linguistics is the use of applied linguistics in legal settings. That definition is extremely broad, but so is the field of study itself. Perhaps it is easier to look at the two words separately. Forensics is when science is used to resolve a legal issue. Linguistics is the scientific study of written and spoken language.

Forensic linguistics then, is any time that written or spoken language is scientifically examined to determine the truth in court or other legal proceedings. Practical applications include times when detectives are attempting to determine who authored a ransom note, or whose voice can be heard in audio recorded during a drug deal.

The words that humans use, whether they are written or spoken, always carry traces of the people using them. You might compare this to a fingerprint, or recall the fact that most people instantaneously recognize the voice of their mother. Despite the fact that there are billions of humans on the planet, we all speak and write in unique ways. It is this uniqueness that forensic linguists look for when using language to solve crimes, to prove the innocence of the wrongfully accused, or to determine the truth in any legal scenario.

Jon Svartvik – author of The Evans Statements: A Case for Forensic Linguistics

The phrase “Forensic Linguistics” was first used in 1968 by a linguistics professor named Jon Svartvik in his book titled The Evans Statements: A Case for Forensic Linguistics. This is actually somewhat shocking in light of the Code of Hammurabi, which is the world’s first law, written sometime between 1792 to 1750 B.C. It’s surprising because humans have been writing, speaking and making laws for several thousand years. It’s hard to imagine that we’ve only just recently generated a term for the analysis of language as it relates to the law. In reality, it is only in name that Forensic Linguistics is a new field. Two ancient examples are pertinent here, one regarding spoken language and the other regarding written language.

A Biblical Example

Shibboleth vs Sibboleth – Judges 12:6

Roger Shuy is widely regarded as one of forensic linguistics’ frontrunners. Shuy often refers to Judges 12:6 as the first recorded use of forensic linguistics in practice. In this passage the Gileadites are faced with the task of weeding out Ephraimite fugitives from amongst their midst after defeating them in battle.

In order to do this, the men from Gilead would ask the men from Ephraim to say the word “Shibboleth” to hear their accent. Men from Ephraim were incapable of saying the word correctly and would instead pronounce it “Sibboleth”, indicating to the Gileadites that they were imposters. As a result, the Gileadites were able to ascertain the identities of these men using a single word.

The Donation of Constantine

Santi Quattro Coronati, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Donation of Constantine is a forged document which was used by the papacy to assert sovereignty over Rome as well as the entire world. Beginning around 800 CE, the Catholic Church claimed the Roman Emperor Constantine had written the document in 315 CE which granted power to Pope Sylvester I, as a way to thank Sylvester for healing Constantine’s leprosy. However, Constantine did not only allegedly grant authority to Sylvester, but to all of his successors until the end of time. Thus, the catholic church continued to abuse the forgery for several hundred years to claim power.

It was not until 1440 CE that the Italian priest and philosopher Lorenzo Valla debunked the document as a forgery. Valla concluded that the Latin used in the document was too poorly written to have been authored by a 4th Century Roman emperor. More specifically, Valla focused on the use of the word “satrap”, which would not yet have been in the vocabulary of someone from the 4th Century. By attending to details in language, Valla essentially employed the same skills Forensic Linguists use, to delegitimize the Donation of Constantine nearly 600 years ago.

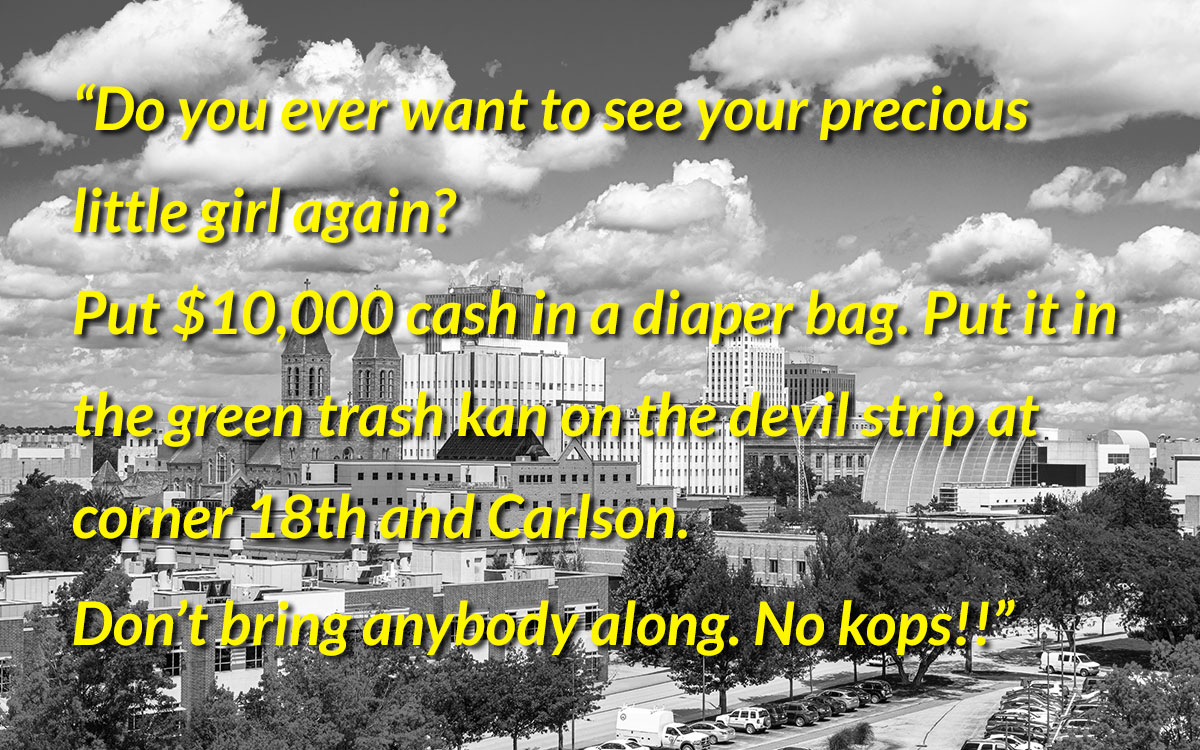

A kidnapping In Ohio

Roger Shy, mentioned above, became prominent in the field of forensic linguistics and was often asked to help resolve criminal cases. In 1979 Shuy was called upon to examine a ransom note in Appleton Ohio which read:

“Do you ever want to see your precious little girl again? Put $10,000 cash in a diaper bag. Put it in the green trash kan on the devil strip at corner 18th and Carlson. Don’t bring anybody along. No kops!!”

There are two key elements in this note which led Shuy to quickly deduce more information about who the kidnapper might be.

Firstly, the term “devil’s strip” is a particularly specific name used to describe the area of grass that lies between a sidewalk and a roadway. This name is actually so specific that it is only used in Akron, Ohio.

Secondly, Shuy noticed that while the words “Kops” and “Kan” were misspelled, more difficult words such as “diaper” and “precious” were spelled correctly. This was a red flag indicating to Shuy that the kidnapper was most likely educated, and only spelled “Kops” and “Kan” incorrectly to make the police believe he was uneducated.

As a result, Shuy asked the police if any of their suspects were educated men from Akron, Ohio. The police indeed had one suspect who fit the description perfectly. When questioned, he confessed.

The Case of Charlene Hummert

In the murder of Charlene Hummert, a linguist named Dr. Robert Leonard noticed nuances in the writing style of the murderer that helped resolve the case. These details allowed Leonard to confirm that several different documents were all written by the same person.

Brian Hummert, Charlene’s spouse, had written two documents which the police called “The Serial Killer Letter”, and “The Stalker” letter during the investigation. These were written with the intention to mislead the police. The stalker letter suspiciously began with this opening sentence, “I killed Charlene Hummert, not her husband.”

Dr. Leonard noticed distinct patterns throughout the documents written to confuse the police, and the way Brian Hummert had written in documents which he’d penned in his own name. There were two distinct things that Brian Hummert did while writing in these nefarious texts and in writings confirmed to be his own.

Firstly, Brian Hummert used a literary device called “ironic repetition” in both documents. One well known example of this comes from Benjamin Franklin: “He that can compose himself, is wiser than he that composes books.” Here, Franklin is using the word “compose” in two different ways. One form of composing is in reference to a person taking care of their inner life. The other version is in reference to someone literally writing a book. It’s ironic because the same word is repeated, but the meaning in both cases is quite different. We’ve chosen to exclude specific examples of Hummert’s ironic repetition here as the imagery is somewhat graphic. Suffice it to say, Hummert used this literary device in writings confirmed to be his own, as well as writings which he had penned under another name.

Secondly, Brian Hummert contracted his verbs in a unique way that revealed his identity. When writing the words “I am”, Hummert chose not to contract the two words. Yet, when writing forms of similar verbs in the negative, Hummert would choose to contract “don’t” or “won’t”. By recognizing the stylistic choices made by Hummert, Dr. Leonard was able to conclude that all the documents were written by the same person. As a result, Hummert was found guilty.

The Innocence of Antwaun Cubie

Forensic linguistics is now being used not only to convict people, but also to prove the innocence of the wrongfully accused. While the case is still in the process of being reviewed, Antwuan Cubie is most likely innocent, and forensic linguistics is being used to bring the facts to light.

In 1996 Antwuan was only 18 when he was accused of shooting his friend in Chicago. By 1999 he had been given a life sentence. The piece of evidence in question is a typed, two page confession which was supposedly dictated by Cubie. Yet, the only thing that Cubie wrote was the signature beneath the two paragraphs. Cubie says that after being beaten by the police to the point of exhaustion, he asked to call his mother. The police officers said he could only do so if he signed and dated a document. Cubie signed a blank page which was later used as the signature for the supposed confession.

The police claimed that the confession was dictated by Cubie and then typed word for word. Yet, when comparing the writing in the written confession, with other known writings authored by Cubie, obvious discrepancies appear. Take for example this phrase from the typed confession: “I met Jeremy at Cass Avenue and 63rd Street in Westmont at an unknown time on Saturday the 1st of June.” It is highly unlikely that an 18 year old would use the phrase “at an unknown time”, especially if he were speaking out loud.

Similarly, the use of the word “then” throughout the confession is suspicious. Take for example this phrase “I then told Jeremy to move his jeep to the end of the alley”, as well as this sentence “we both then went into the building after ringing Jamie’s bell.”

Every time the word “then” was used in the typed confession, it followed the sentence’s subject. When compared to the other known writings of Cubie which totaled 3256 words in length, this way of using the word “then” was not found even once. When Cubie did use the word “then” it was always in a more colloquial sense, that is, preceding the subject of the sentence.

What’s more alarming is the fact that this use of the word “then” closely resembles the writings of the detective testifying against Cubie in his trial. It should be noted that prior to his 1996 arrest, Antwuan Cubie had no criminal record. The use of forensic linguistics to free innocent people is becoming more widespread as the field matures.

The Right To An Interpreter

The importance of having an interpreter during the legal process is impossible to overestimate. This creates difficulties which are particularly prevalent in predominantly English Speaking countries with large immigrant populations. It is already arduous for someone to move to and build a livelihood in a country where their native language is not commonly spoken. However, court proceedings and legal jargon use a far more complicated version of English, which often puts people at a disadvantage when they’re accused of, or charged for illegal activity.

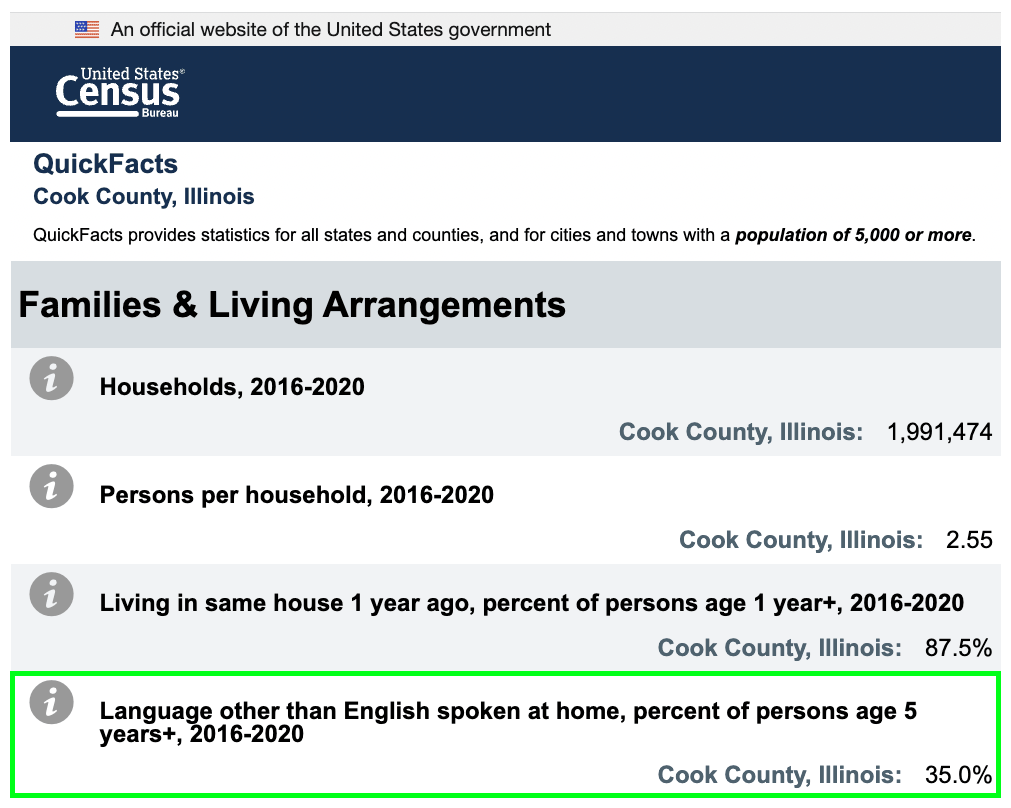

Cook County, Illinois which contains Chicago, is just one example of the imbalance between interpreters in the court systems, and people who are not native English speakers. As of 2021 the population of Cook County was calculated at 5,173,146, with an estimated 35% of that population speaking a language other than English at home. In 2019, the county only had 29 full time interpreters. Yet, one of the busiest courts in the county, Daley Center, has occasion for an average of 66 interpreters on a daily basis.

Cook County, Illinois Census – Families & Living Arrangements

This problem is by no means a new one. In 1974, one case saw a female defendant whose surname was Macias, brought before a magistrate around 2:00 am. Macias spoke no English whatsoever, but was charged with aggravated assault and carrying a concealed weapon. Unable to explain herself, Macias could not communicate the fact that she had no previous criminal record, that she had been dutifully employed for four years, and was the mother of a three year old child, who was at home with a baby-sitter at the time of her arrest.

This is simply one example among thousands and the United States is not the only country to which this issue pertains. The EU in general, Nigeria, and Australia all respectively experience similar issues.

Conclusion

Forensic Linguistics is a vast field of study, and one that is truly impossible to ignore. Given the fact that humanity has always, and will always use language for as long as we exist, Forensic Linguistics will only become more important. The constant use of smartphones to mediate our communication through text and video more and more regularly, means Forensic Linguistics will need to broaden and keep up. Language and law are both quintessentially woven into the fabric of everyday life for humanity. Whether it’s being used to accuse the guilty, or clear the names of the innocent, Forensic Linguistics will surely become more sophisticated as time goes on.