Although it is hard to get an exact number, it is estimated that half of the world’s population is bilingual.[1] The estimate of trilingual people in the world is around 1 billion.[2] If you speak 3 or more languages, you’re known as “multilingual” and you’re much more rare among your fellow humans.[3] No matter what your title is, the cognitive effects of speaking more than one language have been studied by scientists and the results are fascinating.

Cognitive Effects of Speaking Multiple Languages

Science shows us that people who speak more than one language actually comprehend and express reality in more than one way.

One example of this comes from research conducted with people who were fluent in both English and French. In this study, each person was shown a series of illustrations and asked to write a 3 minute story to accompany them. They were asked to write these stories in both English and French but, with 6 weeks separating each time they did so. The study found that in English, the stories contained themes of “female achievement, physical aggression” and “verbal aggression toward parents”. While in French, the stories contained themes of “domination by elders, guilt, and verbal aggression toward peers.”[4]

Another example comes from the way time is conceptualized in multiple languages. Because time is invisible, and difficult to express, people have to use analogies to do so. People who speak Swedish, or English analogously conceive of time in terms of physical distances. For example, in English someone might say “My day was so long”, which conjures images of a tape measure, or road. Whereas, in Greek or Spanish, one might say “My day was so full”, which conjures images of a balloon, a cup of water, or some other container which is meant to be filled.[5]

So what does this mean for people who speak more than one language? It stands to reason that a person who speaks both English and Spanish can conceptualize time as both a distance and a container. Or, if someone speaks both French and English, they might perceive the importance of both female achievement and the voice of elders in their community. If you speak more than one language, you conceive of the world in multiple ways, giving you a more nuanced and varied perspective.

Now, let’s focus on a few examples of how words feel outside of their original language. This is so that even if you don’t speak more than one language fluently, you can still feel the cultural significance of multilingualism for yourself. It is helpful to look at specific examples of loanwords and the reasons they’re used. This will help us grasp the importance of language as a vessel which carries culture. Words don’t only do their obvious job of signaling to an object, person, place, etc… Words also carry emotional and cultural weight. Understanding this will shed more light on the multilingual mind [6]

While there are thousands of ways foreign words can be perceived, here we will explore three categories of words outside of their original language. Those three categories are logical loanwords, ethos loanwords, and untranslatable words.

Logical Loanwords

An argument can be made that all people know a few words from other languages, because words naturally pass between cultures. Examples we use in English are, “Corgi” and “Pizza”, which are not originally English. All languages have these “loanwords”. Loanwords, are words that have been adopted from their original language, into another. [7]

Corgi

Let’s begin with the words “Corgi” and “Pizza”. Languages pragmatically employ loanwords like these, simply because they originate in one language and culture, and there is no need to create a new word in the adoptive language. “Corgi” and “pizza”, are perfect examples of logical loanwords.

In case you don’t know, a Corgi is a breed of dog with amusingly short legs that comes from Wales. In the Welsh language, the name Corgi is a combination of the words “drawf” and “dog”.[8] This makes perfect sense when you see a Corgi. It looks like a dwarfed version of a collie, or some similar dog. It also makes perfect sense that English speakers would not try to generate a new name for the dog breed. The Welsh name “Corgi” fits the dog perfectly and so, we’ve borrowed it.

Pizza

Similarly, Pizza gets its name from its birthplace, which is Italy. Pizza is usually a circular piece of dough that is baked with toppings.[9] Pizza as we’ve come to know it in the modern world originated in Naples, Italy, and has roots as far back as the 1700s. [10] It makes absolute sense that in the English language we would borrow the Italian word, because Pizza is an Italian food.

While there are thousands of examples of other loanwords, “Corgi” and “Pizza” are two simple loanwords with obvious histories. There are, however, other loanwords with more interesting and nuanced histories.

Ethos Loanwords

Ethos is defined as “the fundamental character or spirit of a culture”.[11] This definition succinctly sums up the way words can carry more than the meaning of their direct translation. Let’s look at two examples.

C’est la vie

If you’re in an English speaking country and you hear the words “c’est la vie”, you know that it sort of equates to: “it is what it is”. However, “c’est la vie” carries a particular emotional power with it. The phrase communicates that something uncontrollable has taken place in our lives and we must keep on existing and enduring despite the event.

Usually, “c’est la vie” is used in response to a scenario that is negative. Alysa Salzberg, an American who has lived in Paris for more than a decade, argues that French culture has a style of dealing with tragedy that is particular to France. For example: a newscaster covering a sad or tragic event is only slightly moved, but remains overall, emotionally unscathed.[12] Emily Monaco, another American living in France, says that French people do not readily express joyful emotions in their language. Monaco says, this is not “a mere question of translation, but rather a question of culture”.[13]

Thus the phrase “c’est la vie” is influenced by French culture as a whole, and wraps itself around an entire emotion. “C’est la vie” gathers the sentiment in such an effective way that English speakers are compelled to substitute French words in their vernacular to express their feelings.

Texas

Another example of the way words from a particular culture can perfectly capture an emotion comes from Norway. In 2019 someone on Reddit asked people who are not native English speakers, for examples of English loanwords.

A Norwegian Reddit user said that in Norway, the name of the state of Texas is used as an adjective to describe parties. So, in Norway they might say “that party was ‘Texas!’”, to describe a party which was both massive, as well as “… embarrassing for everybody involved”.[14]

If you’re from the United States, and particularly the southern parts of the United States, it is immediately clear to you why the word “Texas” can easily function as an adjective to describe large, embarrassing parties. There is some essence of wild freedom rolled up in the name “Texas” that perfectly conveys this feeling.

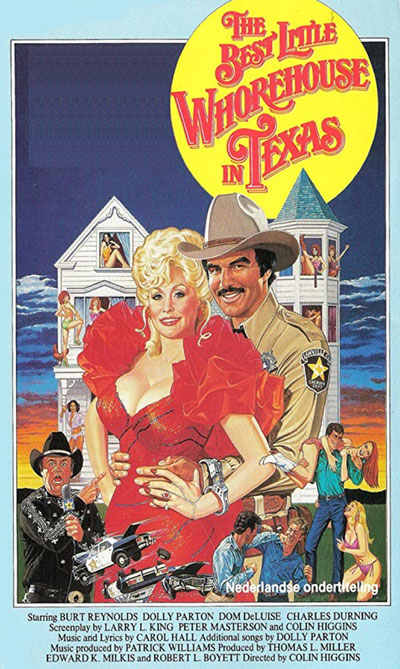

For example, there is a movie entitled, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, starring Burt Reynolds and Dolly Parton. If the title isn’t not enough to convince you that Texas has a big attitude, just look at the film’s poster for a more in-depth impression. The poster features a fist fight, a car chase and a brothel.[15]

In the same way that French culture animates “c’est la vie”, Texan culture animates “Texas”. This cultural phenomenon propels the word “Texas” across the ocean, into the atmosphere of the Norwegian language. Texas’ culture is so eccentric that “Texas” becomes its own adjective because it can’t be expressed more poignantly elsewise.

Untranslatable Words

Sometimes words are inextricably tied to culture. It’s important to consider these words when considering multilingualism. Only the person who speaks the language containing an untranslatable word, can completely understand it.

Saudade

Let’s look at the untranslatable Portuguese word “Saudade”. Some have translated “Saudade” as a melancholic longing for someone or something that is absent.[16] Audrey Bell, a Portuguese scholar, says that Saudade is a “vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present.”[17] One thing seems to be certain about this word: it cannot be understood outside of its cultural context.

Gökotta

“Gökotta” is another untranslatable word that comes from Sweden. This word means “to rise at dawn in order to go out and listen to the birds sing.” The word is specifically Swedish because of the tradition which birthed it. In some parts of Sweden, it is customary to go into nature on Ascension day, the 40th day after Easter and listen to birds sing in the morning. Like “saudade”, the word is tethered to its roots in a way that makes it nearly impossible to use in another language.[18]

Final Thoughts

The meaning of words vary in depth and difficulty to comprehend. Logical loanwords like “Corgi” and “Pizza” seem to fall on the easier end of the spectrum because they’re simple to understand in any language. A Corgi is a dwarf dog, a Pizza is an Italian, baked, dough covered in toppings.

Ethos loanwords, “Texas” and “C’est la vie”, carry emotional and cultural value which translate with a bit more effort. We can have a vague understanding of a phrase like “c’est la vie” even if we do not speak French, because we’ve often heard the term contextualized in English. Similarly, party-goers in Norway seem to have gleaned something about the nature of Texas which still rings true for us at home. “Texas” and “C’est la vie”, are not just phrases, they are ideas with a life of their own.

“Saudade” and “Gökotta” are examples of the final frontier of language. These are entire emotions that one cannot conceive without being exposed to the culture in which the feeling, and the word originated. So, if you have time and want to open your mind not only to new words, but to new histories, cultures, analogies for time, and even emotions, learn to speak a new language. Become part of the half of the world’s population that has a more broad and nuanced conception of reality.

- [1]https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/half-the-world-is-bilingual-whats-our-problem/2019/04/24/1c2b0cc2-6625-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html

- [2] https://www.rosettastone.com/languages/trilingual

- [3] http://ilanguages.org/bilingual.php

- [4] https://newrepublic.com/article/117485/multilinguals-have-multiple-personalities

- [5] https://www.popsci.com/language-time-perception/

- [6] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/01/190109110040.htm

- [7]https://www.ruf.rice.edu/~kemmer/Words04/structure/borrowed.html.

- [8] https://www.etymonline.com/word/corgi

- [9] https://www.britannica.com/topic/pizza

- [10] https://www.history.com/news/a-slice-of-history-pizza-through-the-ages

- [11] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/ethos

- [12] https://frenchtogether.com/cest-la-vie/

- [13] https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20181104-why-the-french-dont-show-excitement

- [14] https://www.buzzfeed.com/daniellaemanuel/english-words-other-countries

- [15] https://padresteve.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/the-best-little-whorehouse-in-texas.jpg

- [16] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/saudade

- [17] https://amaliahomecollection.com/the-meaning-of-saudade-the-most-portuguese-word/

- [18] https://www.203challenges.com/the-swedish-concept-of-gokotta-listen-to-the-morning-birdsong/